Particularly in the winter months, I am one of those people who are constantly checking the weather forecast. Is it going to snow or rain? How cold will it be? Can I get out for a walk when there is no precipitation? How much clothes do I need to wear? I consult my weather app on my phone daily, if not several times a day. I’ve also noted that the weather forecasts are much more detailed (it will rain for the next 90 minutes and then clear up) and more accurate (it actually does rain for 90 minutes then stop).

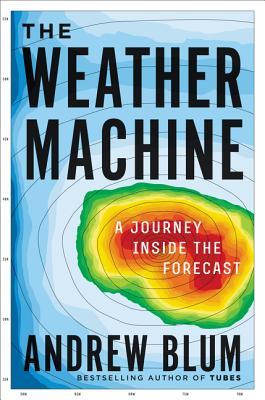

I found this book by Andrew Blum very interesting as he goes into the history of weather forecasting and how it has come to the point it is now, with very reliable forecasts for the next 24 hours. If you find this topic interesting, I recommend this book. It is relatively short (about 130 pages of text) and well written. The language is simple so that anyone can understand what he is writing about and he has stories of people which make it easier to connect to the history he is telling. If you don’t like spoilers, you can hop over the rest of this blog. If you want to learn more about the book and its contents, continue reading, as I will summarize the main points of the book. Many of the expressions that I use in my own text are taken from Blum’s book.

Much of the book is about the history of how weather forecasting developed and as a resident of Norway, I found it interesting how much Norway was part of this history. The Prologue gives his reasons for investigating this topic, then the book is divided into four parts:

- Part I: Calculation – two chapters

- Part II: Observation – four chapters

- Part III: Simulation – four chapters

- Part IV: Preservation – one chapter

Part I: Calculation

The book starts off with a visit to the Norwegian Meteorological Institute in Oslo in June 2015. Because Norwegians are at the mercy of the cold and the wind, and is a relatively rich country, forecasting the weather and understanding the mechanics of the atmosphere has had a long tradition in Norway.

With the invention of the telegraph in 1844, communication between various points in a country became much easier and current weather conditions could be compared with places far away. People’s understanding of weather began to develop and it wasn’t just what people were experiencing right then. A map could be made of what the weather looked like. Seeing a map of what was happening allowed people to start thinking about probable changes and therefore how the weather might be in the future.

So the collection of weather observations became part of the weather service. The collection and sharing of this information was the next development. In 1873, the first congress of what later became the International Meteorological Organization took place in Vienna with representatives from twenty governments. Standards, protocols and rules were developed.

By 1895, just the collection of weather observations was not enough, it had to be put into a new system of understanding how the weather worked. Vilhelm Bjerknes, a Norwegian, took this understanding one step farther by suggesting that the weather could be calculated using physics and mathematics, making meteorology a modern science: verifiable, repeatable and mathematical. Bjerknes’ equations weren’t easy to solve, but it was a start towards understanding the connection between the atmosphere and the weather.

This led to the idea of a weather factory where calculations were made, based on weather observations, that could lead to a forecast of what the weather would be like in the future.

Part II: Observation

The first chapter in this part of the book is about how weather observations are made. Some weather stations are manned as there are some observations that only a human can do. Some observations are made on land, some on the sea, some on aircraft and some from satellites. The author decides to visit a manned weather station and visits the island of Utsira off the west coast of Norway, between Bergen and Stavanger. This has been a weather station since the 1860s. Things that Hans Van Kampen must record, several times a day, include type of precipitation, sky height, visibility and cloud type.

The second chapter in this part is how the view of the weather changed, driven by technological developments and military needs, primarily in World War II. Among other developments was the sending up of rockets with cameras mounted on them, taking pictures of the earth that they were leaving. Now came the idea of having instruments up in the atmosphere, above the clouds, to get a larger view of the weather systems. Such was the start of weather satellites that are now used as one type of weather observations. The World Weather Watch was born and was to be used for peaceful purposes only, as the atmosphere is borderless.

The third chapter in this part describes the two types of weather satellites, geostationary orbiters (which appear motionless as they follow the earth’s rotation) and polar orbiters (which fly lower and circle the planet from north to south and from south to north). Most of these satellites are owned by governments. In Europe, EUMETSAT, the European meteorological satellite agency is an independent organization funded and overseen by the meteorological services of thirty nations.

The fourth chapter in this part gives more information about satellites, how they are made and what they do, including a visit to Vandenberg, in California, to see the launch of a satellite.

Part III: Simulation

In the first chapter in this part, the author visits the Mesa Lab, outside Boulder, Colorado, where we are given information about how the weather models work, how the observations are used and turned into a forecast of what most likely will happen in the future. Supercomputers are now used to take the observations and make calculations, and provide reliable forecasts of what will happen in the near future. These weather models are constantly being tweaked to improve them.

In the second chapter of this part, the author travels to the Weather Centre in Reading, England, actually called the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), which opened in 1979. (This is also the source of the weather forecasts used in Norway by yr.no.) We are given information about the history of this centre, plus we get insights into how it works. What is impressive is how the model that is being run here becomes more accurate as time goes on. This chapter gives interesting insights into how such a weather center functions and how forecasts are created by supercomputers.

The third chapter of this part discusses how weather forecasts have become available to us users since the first forecast appeared on the internet in 1991. The importance of forecasts is in being able to use them. The introduction of smart phones changed the need to have forecasts available constantly, and not just once a day for the evening news on television.

The four chapter in this part is about what makes a good weather forecast as well as what a weather forecast is good for. The weather forecast is being primarily generated by computers, but humans are still need to get the information out to users, whether it is an individual needing to know whether it’s going to rain, or the media that can warn the general public of a major storm that is coming, or emergency services that have to be prepared for the big storm that creates problems.

Part IV: Preservation

The last chapter of the book is concerned with the future of weather forecasting and who is in control of it. Though forecasting has improved a lot in recent years, there are still a lot of hurdles in the way. One of the concerns is who owns the data that is being generated, whether it is individual observations or observations made by private networks. International cooperation has been the basis of the work so far, but will this cooperation continue into the future?

To quote Blum’s conclusion: “The weather machine is a last bastion of international cooperation. It produces some of the only news that isn’t corrupted by commerce, by advertising, by bias or fake-ness. It is one of the technological wonders of the world. At the beginning of an era when the planet will be wracked by storms, droughts, and floods that will threaten if not shred the global order, the existence of the weather machine is some consolation.”

I really enjoyed this book and I recommend it to all of my readers. Enjoy!